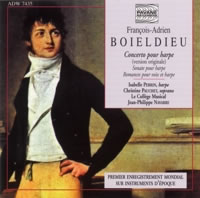

François-Adrien Boieldieu by Isabelle Perrin

|

| Artist Profile and index of recordings and sheet music |

| Concerto in C major for Harp and Orchestra | ||

| 1 | Allegro brillante | 11.17 |

| 2 | Lento | 3.39 |

| 3 | Rondeau : Agitato | 7.06 |

| Sonata in G major, Opus 8 No. 2, for solo Harp | ||

| 4 | Allegro | 7.56 |

| 5 | Rondo : Allegretto | 7.04 |

| Romances for Voice and Harp | ||

| 6 | Quoi, tu m'aimes | 3.49 |

| 7 | Dans le printemps de mes années | 5.38 |

| 8 | Les Souvenirs | 2.36 |

| 9 | Les femmes justifées | 4.45 |

| 10 | La dormeuse | 2.45 |

| 11 | L'Amour, pour prix de ma défaite | 3.44 |

Total

Time |

60.57 |

|

Sleeve Notes

Boieldieu

a musician between Monarchy and Revolution

By Jean-Philippe Navarre

A native of Rouen, François-Adrien Boieldieu received his earliest musical training from Charles Broche, the cathedral organist at Rouen. He turned quickly towards vocal music, especially opera. But, in the beginnings of his career, instrumental music was also important for him, judging from his output in this field: sonatas for the pianoforte, duos for harp and forte piano, variations and concertos. As a virtuoso on the pianoforte, Boieldieu was appointed, some months after his arrival in Paris, professor at the newly founded Conservatoire. Among his pupils, we note François-Joseph Fétis. The success of his operas, going up to the famous Dame Blanche, was durable and established him as one of the principal French dramatic composers.

Surely, Berlioz was unfair to him, when he describes Boieldieu in his Memoirs. The reality stays as far as he reported it, and also as some biographers, especially Faure, drew up. In the chapter XXV of his Memoirs, Berlioz relates a talk he had with Boieldieu, just after the 1829 Prix de Rome competition : « Boieldieu, in this naive talk, epitomized the French ideas on musical art. People, in Paris, wanted a delightful music, regardless to the most awesome situations, they wanted music just a little dramatic, not too clear, colourless, without extraordinary harmonies, without unusual rhythms, unusual forms, unusual effects, a music without difficulties and requiring no special attention, simple both for performers and listeners — a pleasant and elegant art, never dreaming and passionate, but fresh and lively. »

A great portion of Boieldieu’s music follows these principles.

A lot of passages in his operas, and a large part of the Dame Blanche (the

success of which is actually related to the libretto, from the book by

Walter Scott), offer notes and notes again, over poor harmonies. Only

the instrumentation save the whole from a complete disaster. In Boieldieu’s

output, the earliest works are the most interesting. In the first pianoforte

sonatas, we find some invention and expression which denote a peculiar

genius, between Mozart and the young Beethoven.

Of the two concertos composed by Boieldieu— a pianoforte concerto in F major and the harp concerto in C major — only the second is truly interesting. Against Berlioz statement, the harp concerto shows a learned harmony, an enlarged form, unusual rhythmic vivacity and orchestral effects.

In a way, Boieldieu brought up this concerto to a summit in the kind. Taking the division in three movements, he gave an astonishing fullness to the first (in C major), refined the traditional lied devoted to second movements and linked it, with a cadenza (who had to be normally placed at the end of the first movement), to the the final rondo in the key of C minor. By closing the concerto in a minor key, regardless to the major one of the first movement, Boieldieu escapes from the conventions of classicism. It is a romantic tone.

When we compare the concerto with the G major sonata for harp solo, opus

8 no. 2 (c. 1807), the latter seems very traditional. Sometimes Beethovenian

features appear massive low-pitched chords, rhythmic and melodic elements

developed. But French art towards 1800 refuses complexity, and Boieldieu

shows less invention in his opus 8 than in the sonatas opus 1, 2 and

3. This piece, without an andante or adagio, is naturally pleasant

and elegant. Composed for the fortepiano or harp, the G major sonata

has a violin accompaniment ad lib., a great tradition in France

dating from c. 1760.

Boieldieu published sixteen collections of Romances, i.e. around one hundred of these little pieces. His first publication, in 1794, are Romances. The French Revolution’s taste showed a great favour for the romance, a kind of gentle poetry with simple music, illustrated by Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Modeste Grétry. The sentimental character of the text — sometimes in the form of moral lesson — combines with a very simple melodic and harmonic scheme. We can notice, among the greatest achievements, romances on three or four notes. These characteristics allowed a large circulation by avoiding vocal or intonation difficulties. The six Romances of Boieldieu included in the present recording date from 1794 to 1803. They adopt the stophic form, with or without refrain. These small pieces show another face of Boieldieu’s melodic genius nonetheless, the Harp Concerto appears in Boieldieu’s output as a fascinating and exceptional work.

(translated by Jean-Philippe Navarre)

Boieldieu’s Harp Concerto

History of a reconstruction

by Jean-Philippe Navarre

When I took an interest in Boieldieu’s Harp Concerto in the years 1987-88, I discovered it in the arrangement by Carl Stüber, published by Ricordi. Quickly, I tried to find the original edition. According to Georges Favre’s statement in his book on Boieldieu, I found only one incomplete set of parts, located at she Brussels library of the Conservatoire Royal. After a long survey in the main French and European libraries, I was convinced that the hope so discover a complete set of parts was actually very thin and that I needed to reconstruct the concerto in a manner stylistically nearest to ancient practices, the Stüber version being by far anachronistic.

My work began with a systematic exploration of Boieldieu’s orchestral characteristics. After this stage, I analysed closely the instrumental colour of the fortepiano concerto in F, this work existing in a complete set of parts. Two elements were retained : the limited number of parts (strings, two oboes, two horns) and the fact that the finale is the same as the finale of one Duo for fortepiano and harp. I noticed in the latter that the notation of harp and pianoforte was nearly the same.

A second state of research concerned the harp methods published in France

during Boieldieu’s musical activity, in order to improve Boieldieu

harp notation. In fact, the concerto shows two peculiar characteristics

tills to be played with the right hand only (the left hand playing

other notes), and long scales series in octava. Cousineau’s and

Genlis’s methods gave very difficult examples in this kind, long

before the concerto’s. Isabelle Perrin and I have chosen to play

the concerto in his original form, except very few passages unplayable

on the simple action harp (some chromatic formulas in the second movement

for example).

Played in this original version, the concerto appears very brilliant and the orchestra is more transparent. Isabelle Perrin performed this version on the 14 of December 1994, in Grenoble and I conducted the Ensemble Instrumental de Grenoble in my arrangement of the orchestral accompaniment. The present recording takes advantage of period instruments. The sitting plan of the orchestra agrees with ancient practices (first violin on the left side, second violins on the right side, violas and basses in front of the conductor, winds behind them). The recording was made with two microphones and keep the original balance between the soloist and the orchestra.

(translated by Jean-Philippe Navarre)

Instrumentation

HARP

HARP

Isabelle PERRIN: Beat Wolf, 1995 (37 cordes. simple mouvement, mécanique à

béquilles, d’après divers modèles de la

fin du dix-huitième siècle).

VIOLIN

Frédéric DAUDIN-CLAVAUD: Jean-François Aldric.

Paris, 1800

Caroline LECOUFFE: Joan Eherll, Prague, 1761

Yasmine HAMMANI: École de Hopf, c. 1800

Nicolas DESMALINES: Georges Klotz, Mittenwald, 1723

Agnès FOSSE: Nicolas-Augustin Chapuis, Paris, c. 1760

Pauline DANGLETERRE: Famille Klotz « raccommodé par

Chalon en 1816 »

Céline PLANTARD: Jean-Baptiste Grandgérard, Mirecourt,

c.1800

VIOLA

Bernard GAUDFROY: François Lejeune, Paris. 1755 (recoupé Mirecourt

en 1800)

Max DUPUIS: Jean Grosselet, Mirecourt, c. 1800

VIOLONCELLO

Catherine RAMONA: Anonyme, France, c. 1810

Emilia GLIOZZI: Paolo Galetti, Crémone, e. 1770

DOUBLE BASS

Sylvain COURTEIX: Anonyme, Mirecourt, c. 1900

OBOE

Michel HENRY: Olivier Cottet, d’après Grundmann & Floth

Daniel SCHIRRER: Olivier Cottet, d’après Grenzer

HORN

Yves TRAMON: Millereau, modèle Raoux, c. 1850

Pierre DELCOUR: Millereau, modèle Raoux, c. 1850

Credits

Recorded at Théâtre

de Douai 3-5 January 2000

Engineering Michel Dehaye

Mixing Manuel Mohino

Artistic Director: Jean-Philippe Navarre

Produced by Bertrand de Wouters d'Oplinter

Cover Portrait: François-Adrien Boieldieu, by L.-L Biolly (1800)

| Instruments: | Harp, Voice, Orchestra |

| Genre: | Classical |

| Format: | Audio CD [DDD] |

| Our Ref: | A0166 |

| MCPS: | ADW 7435 |

| Label: | Pavane Records |

| Year: | 2000 |

| Origin: | France |